Chapter 14. The Exhibition

Chapter 14. The Exhibition

The next day, when they came to the exhibition, Lady Delacour had an opportunity of judging of Belinda’s real feelings. As they went up the stairs, they heard the voices of Sir Philip Baddely and Mr. Rochfort, who were standing upon the landing-place, leaning over the banisters, and running their little sticks along the iron rails, to try which could make the loudest noise.

“Have you been much pleased with the pictures, gentlemen?” said Lady Delacour, as she passed them.

“Oh, damme! no–’tis a cursed bore; and yet there are some fine pictures: one in particular–hey, Rochfort?–one damned fine picture!” said Sir Philip. And the two gentlemen laughing significantly, followed Lady Delacour and Belinda into the rooms.

“Ay, there’s one picture that’s worth all the rest, ‘pon honour!” repeated Rochfort; “and we’ll leave it to your ladyship’s and Miss Portman’s taste and judgment to find it out, mayn’t we, Sir Philip?”

“Oh, damme! yes,” said Sir Philip, “by all means.” But he was so impatient to direct her eyes, that he could not keep himself still an instant.

“Oh, curse it! Rochfort, we’d better tell the ladies at once, else they may be all day looking and looking!”

“Nay, Sir Philip, may not I be allowed to guess? Must I be told which is your fine picture?– This is not much in favour of my taste.”

“Oh, damn it! your ladyship has the best taste in the world, every body knows; and so has Miss Portman–and this picture will hit her taste particularly, I’m sure. It is Clarence Hervey’s fancy; but this is a dead secret–dead–Clary no more thinks that we know it, than the man in the moon.”

“Clarence Hervey’s fancy! Then I make no doubt of its being good for something,” said Lady Delacour, “if the painter have done justice to his imagination; for Clarence has really a fine imagination.”

“Oh, damme! ’tis not amongst the history pieces,” cried Sir Philip; “’tis a portrait.”

“And a history piece, too, ‘pon honour!” said Rochfort: “a family history piece, I take it, ‘pon honour! it will turn out,” said Rochfort; and both the gentlemen were, or affected to be, thrown into convulsions of laughter, as they repeated the words, “family history piece, ‘pon honour!–family history piece, damme!”

“I’ll take my oath as to the portrait’s being a devilish good likeness,” added Sir Philip; and as he spoke, he turned to Miss Portman: “Miss Portman has it! damme, Miss Portman has him!”

Belinda hastily withdrew her eyes from the picture at which she was looking. “A most beautiful creature!” exclaimed Lady Delacour.

“Oh, faith! yes; I always do Clary the justice to say, he has a damned good taste for beauty.”

“But this seems to be foreign beauty,” continued Lady Delacour, “if one may judge by her air, her dress, and the scenery about her–cocoa-trees, plantains: Miss Portman, what think you?”

“I think,” said Belinda, (but her voice faltered so much that she could hardly speak,) “that it is a scene from Paul and Virginia. I think the figure is St. Pierre’s Virginia.”

“Virginia St. Pierre! ma’am,” cried Mr. Rochfort, winking at Sir Philip. “No, no, damme! there you are wrong, Rochfort; say Hervey’s Virginia, and then you have it, damme! or, may be, Virginia Hervey–who knows?”

“This is a portrait,” whispered the baronet to Lady Delacour, “of Clarence’s mistress.” Whilst her ladyship leant her ear to this whisper, which was sufficiently audible, she fixed a seemingly careless, but most observing, inquisitive eye upon poor Belinda. Her confusion, for she heard the whisper, was excessive.

“She loves Clarence Hervey–she has no thoughts of Lord Delacour and his coronet: I have done her injustice,” thought Lady Delacour, and instantly she despatched Sir Philip out of the room, for a catalogue of the pictures, begged Mr. Rochfort to get her something else, and, drawing Miss Portman’s arm within hers, she said, in a low voice, “Lean upon me, my dearest Belinda: depend upon it, Clarence will never be such a fool as to marry the girl–Virginia Hervey she will never be!”

“And what will become of her? can Mr. Hervey desert her? she looks like innocence itself–and so young, too! Can he leave her for ever to sorrow, and vice, and infamy?” thought Belinda, as she kept her eyes fixed, in silent anguish, upon the picture of Virginia. “No, he cannot do this: if he could he would be unworthy of me, and I ought to think of him no more. No; he will marry her; and I must think of him no more.”

She turned abruptly away from the picture, and she saw Clarence Hervey standing beside her.

“What do you think of this picture? is it not beautiful? We are quite enchanted with it; but you do not seem to be struck with it, as we were at the first glance,” said Lady Delacour.

“Because,” answered Clarence, gaily, “it is not the first glance I have had at that picture–I admired it yesterday, and admire it to-day.”

“But you are tired of admiring it, I see. Well, we shall not force you to be in raptures with it–shall we, Miss Portman? A man may be tired of the most beautiful face in the world, or the most beautiful picture; but really there is so much sweetness, so much innocence, such tender melancholy in this countenance, that, if I were a man, I should inevitably be in love with it, and in love for ever! Such beauty, if it were in nature, would certainly fix the most inconstant man upon earth.”

Belinda ventured to take her eyes for an instant from the picture, to see whether Clarence Hervey looked like the most inconstant man upon earth. He was intently gazing upon her; but as soon as she looked round, he suddenly exclaimed, as he turned to the picture–“A heavenly countenance, indeed!–the painter has done justice to the poet.”

“Poet!” repeated Lady Delacour: “the man’s in the clouds!”

“Pardon me,” said Clarence; “does not M. de St. Pierre deserve to be called a poet? Though he does not write in rhyme, surely he has a poetical imagination.”

“Certainly,” said Belinda; and from the composure with which Mr. Hervey now spoke, she was suddenly inclined to believe, or to hope, that all Sir Philip’s story was false. “M. de St. Pierre undoubtedly has a great deal of imagination, and deserves to be called a poet.”

“Very likely, good people!” said Lady Delacour; “but what has that to do with the present purpose?”

“Nay,” cried Clarence, “your ladyship certainly sees that this is St. Pierre’s Virginia?”

“St. Pierre’s Virginia! Oh, I know who it is, Clarence, as well as you do. I am not quite so blind, or so stupid, as you take me to be.” Then recollecting her promise, not to betray Sir Philip’s secret, she added, pointing to the landscape of the picture, “These cocoa trees, this fountain, and the words Fontaine de Virginie, inscribed on the rock–I must have been stupidity itself, if I had not found it out. I absolutely can read, Clarence, and spell, and put together. But here comes Sir Philip Baddely, who, I believe, cannot read, for I sent him an hour ago for a catalogue, and he pores over the book as if he had not yet made out the title.”

Sir Philip had purposely delayed, because he was afraid of rejoining Lady Delacour whilst Clarence Hervey was with her, and whilst they were talking of the picture of Virginia.

“Here’s the catalogue; here’s the picture your ladyship wants. St. Pierre’s Virginia: damme! I never heard of that fellow before–he is some new painter, damme! that is the reason I did not know the hand. Not a word of what I told you, Lady Delacour–you won’t blow us to Clary,” added he aside to her ladyship. “Rochfort keeps aloof; and so will I, damme!”

A gentleman at this instant beckoned to Mr Hervey with an air of great eagerness. Clarence went and spoke to him, then returned with an altered countenance, and apologized to Lady Delacour for not dining with her, as he had promised. Business, he said, of great importance required that he should leave town immediately. Helena had just taken Miss Portman into a little room, where Westall’s drawings were hung, to show her a group of Lady Anne Percival and her children; and Belinda was alone with the little girl, when Mr Hervey came to bid her adieu. He was in much agitation.

———————————————-

Maria Edgeworth, 1768-1849

Title: Belinda,1801

Maria Edgworth, 1768-1849, was a British writer, associated with the Anglo-Irish Tory gentry, notable for her observations on social conventions through well-observed dialogue and challenging moral views on the politics, Catholic emancipation, agricultural reform, education, anti-semitism and the role of property and the injustices caused by English and Irish absentee landlords. Her major novels are Castle Rackrent, 1800; Belinda, 1801; Leonora, 1806; The Absentee, 1812; Patronage,1814; and Harrington, 1817; Ormond, 1817.

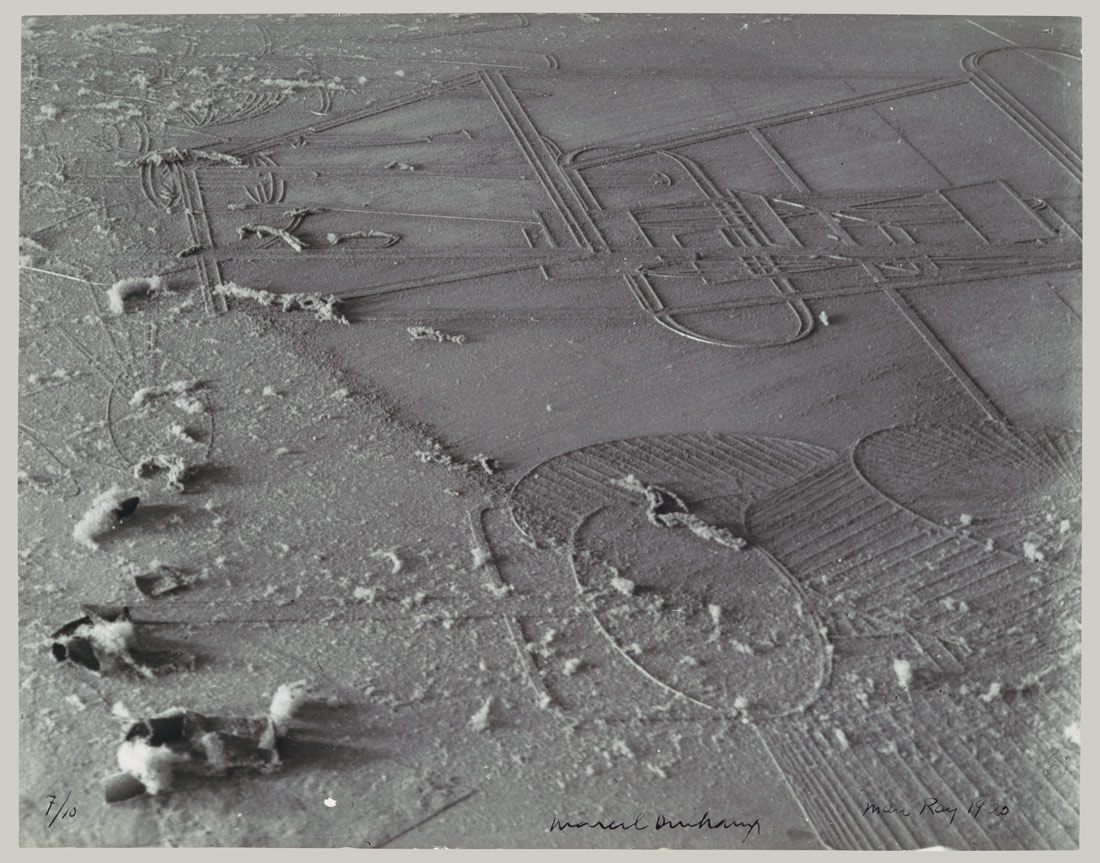

The novel Belinda, 1801, was considered controversial in its day, owing to its depiction of interracial marriage. In the 1810 publication, some characters were replaced and the interracial plot lines were omitted completely. In ‘The Exhibition’, chapter 14 of Belinda, during a visit by Lady Delacour to the picture gallery of Clarence Hervey, she is directed to a picture of ‘Paul and Virginie’ illustrating a scene from Jacques-Henri Bernadin de Saint-Pierre’s novel ‘Paul et Virginie’, 1788 set on the French colony of Ile-de-France (Mauritius). The novel tells the story of two childhood friends who become lovers, and is an Enlightenment story of a child of nature whose moral views are corrupted by the false sentimentality of the French bourgeoisie and aristocracy on the eve of the French Revolution.

Lady Delacour, who is a mercenary rival suitor to Belinda for the hand and estate of Clarence Hervey, is advised by Sir Phillip Baddely that the picture is of Mr Hervey’s ‘native’ mistress. As part of the intrigue, Mr Hervey warns Belinda as a friend that it is being rumoured that Belinda would marry Lord Delacour after his wife’s death. Belinda is a traditional courtship novel of the period where women might seek socially suitable fortune-hunting marriages. Belinda is a Romantic heroine who champions innocence, love and feelings over marital duty and compatibility in a treatment of themes popularised by Jane Austen.

In Chapter XXV of her novel ‘Patronage’, 1814, Edgeworth portrays the importance of painting as a symbol of lineage and marriageability in the sentence, “A picture is no very dangerous rival, except in a modern novel.”

The characters

Belinda Portman – the heroine

Mrs Stanhope – Belinda’s matchmaking aunt

Lady Delacour – the society hostess with whom Belinda stays in London

Lord Delacour – Lady Delacour’s dissolute husband

Clarence Hervey – Belinda’s suitor #1

Sir Philip Baddeley – one of Mr Hervey’s dissipated friends and Belinda’s suitor #2

Mr Rochfort – another of Mr Hervey’s dissipated friends

Mr Vincent – Belinda’s suitor #3 – a rich West Indian gentleman

Mr Henry Percival – a gentleman who once loved Lady Delacour, but who has found happiness in his second attachment

Lady Anne Percival – Mr Percival’s wife, seemingly the perfect wife and mother

Helena Delacour – Lady Delacour’s only surviving child

Margaret Delacour – Lord Delacour’s sister

Mrs Luttridge – Lady Delacour’s rival

Mrs Harriet Freke – once Lady Delacour’s friend, but now her bitterest enemy

Marriott – Lady Delacour’s maid

Champfort – Lord Delacour’s manservant

Virginia St Pierre – a young woman living under Mr Hervey’s protection

Mrs Ormond – Virginia’s companion

Mr Moreton – a clergyman who was badly treated by Harriet Freke but rewarded by Mr Hervey

Mr Hartley – Virginia’s father

Images: 1. Maria Edgeworth – Belinda. Belinda at the exhibition. 1896

2. Paul et Virginie

Chapter 14. The Exhibition

Chapter 14. The Exhibition

PART TWO. THE JOURNEY

PART TWO. THE JOURNEY

Chapter 3 – GERTRUDE STEIN IN PARIS

Chapter 3 – GERTRUDE STEIN IN PARIS

You must be logged in to post a comment.