Chapter 1

Chapter 1

In the better and wiser tone of feeling with Ovid only expresses in one line to retract in that which follows, I can address these quires–

Parve, nec invideo, sine me, liber, ibis in urbem.

Nor do I join the regret of the illustrious exile, that he himself could not in person accompany the volume, which he sent forth to the mart of literature, pleasure, and luxury. Were there not a hundred similar instances on record, the rate of my poor friend and school-fellow, Dick Tinto, would be sufficient to warn me against seeking happiness in the celebrity which attaches itself to a successful cultivator of the fine arts.

Dick Tinto, when he wrote himself artist, was wont to derive his origin from the ancient family of Tinto, of that ilk, in Lanarkshire, and occasionally hinted that he had somewhat derogated from his gentle blood in using the pencil for his principal means of support. But if Dick’s pedigree was correct, some of his ancestors must have suffered a more heavy declension, since the good man his father executed the necessary, and, I trust, the honest, but certainly not very distinguished, employment of tailor in ordinary to the village of Langdirdum in the west.. Under his humble roof was Richard born, and to his father’s humble trade was Richard, greatly contrary to his inclination, early indentured. Old Mr. Tinto had, however, no reason to congratulate himself upon having compelled the youthful genius of his son to forsake its natural bent. He fared like the school-boy who attempts to stop with his finger the spout of a water cistern, while the stream, exasperated at this compression, escapes by a thousand uncalculated spurts, and wets him all over for his pains. Even so fared the senior Tinto, when his hopeful apprentice not only exhausted all the chalk in making sketches upon the shopboard, but even executed several caricatures of his father’s best customers, who began loudly to murmur, that it was too hard to have their persons deformed by the vestments of the father, and to be at the same time turned into ridicule by the pencil of the son. This led to discredit and loss of practice, until the old tailor, yielding to destiny and to the entreaties of his son, permitted him to attempt his fortune in a line for which he was better qualified.

There was about this time, in the village of Langdirdum, a peripatetic brother of the brush, who exercised his vocation sub Jove frigido, the object of admiration of all the boys of the village, but especially to Dick Tinto. The age had not yet adopted, amongst other unworthy retrenchments, that illiberal measure of economy which, supplying by written characters the lack of symbolical representation, closes one open and easily accessible avenue of instruction and emolument against the students of the fine arts. It was not yet permitted to write upon the plastered doorway of an alehouse,. or the suspended sign of an inn, “The Old Magpie,” or “The Saracen’s Head,” substituting that cold description for the lively effigies of the plumed chatterer, or the turban’d frown of the terrific soldan. That early and more simple age considered alike the necessities of all ranks, and depicted the symbols of good cheer so as to be obvious to all capacities; well judging that a man who could not read a syllable might nevertheless love a pot of good ale as well as his better-educated neighbours, or even as the parson himself. Acting upon this liberal principle, publicans as yet hung forth the painted emblems of their calling, and sign-painters, if they seldom feasted, did not at least absolutely starve.

To a worthy of this decayed profession, as we have already intimated, Dick Tinto became an assistant; and thus, as is not unusual among heaven-born geniuses in this department of the fine arts, began to paint before he had any notion of drawing.

His talent for observing nature soon induced him to rectify the errors, and soar above the instructions, of his teacher. He particularly shone in painting horses, that being a favourite sign in the Scottish villages; and, in tracing his progress, it is beautiful to observe how by degrees he learned to shorten the backs and prolong the legs of these noble animals, until they came to look less like crocodiles, and more like nags. Detraction, which always pursues merit with strides proportioned to its advancement, has indeed alleged that Dick once upon a time painted a horse with five legs, instead of four. I might have rested his defence upon the license allowed to that branch of his profession, which, as it permits all sorts of singular and irregular combinations, may be allowed to extend itself so far as to bestow a limb supernumerary on a favourite subject. But the cause of a deceased friend is sacred; and I disdain to bottom it so superficially. I have visited the sign in question, which yet swings exalted in the village of Langdirdum; and I am ready to depone upon the oath that what has been idly mistaken or misrepresented as being the fifth leg of the horse, is, in fact, the tail of that quadruped, and, considered with reference to the posture in which he is delineated, forms a circumstance introduced and managed with great and successful, though daring, art. The nag being represented in a rampant or rearing posture, the tail, which is prolonged till it touches the ground, appears to form a point d’appui, and gives the firmness of a tripod to the figure, without which it would be difficult to conceive, placed as the feet are, how the courser could maintain his ground without tumbling backwards. This bold conception has fortunately fallen into the custody of one by whom it is duly valued; for, when Dick, in his more advanced state of proficiency, became dubious of the propriety of so daring a deviation to execute a picture of the publican himself in exchange for this juvenile production, the courteous offer was declined by his judicious employer, who had observed, it seems, that when his ale failed to do its duty in conciliating his guests, one glance at his sign was sure to put them in good humour.

It would be foreign to my present purpose to trace the steps by which Dick Tinto improved his touch, and corrected, by the rules of art, the luxuriance of a fervid imagination. The scales fell from his eyes on viewing the sketches of a contemporary, the Scottish Teniers, as Wilkie has been deservedly styled. He threw down the brush. took up the crayons, and, amid hunger and toil, and suspense and uncertainty, pursued the path of his profession under better auspices than those of his original master. Still the first rude emanations of his genius, like the nursery rhymes of Pope, could these be recovered, will be dear to the companions of Dick Tinto’s youth. There is a tankard and gridiron painted over the door of an obscure change-house in the Back Wynd of Gandercleugh—-But I feel I must tear myself from the subject, or dwell on it too long.

Amid his wants and struggles, Dick Tinto had recourse, like his brethren, to levying that tax upon the vanity of mankind which he could not extract from their taste and liberality–on a word, he painted portraits. It was in this more advanced state of proficiency, when Dick had soared above his original line of business, and highly disdained any allusion to it, that, after having been estranged for several years, we again met in the village of Gandercleugh, I holding my present situation, and Dick painting copies of the human face divine at a guinea per head. This was a small premium, yet, in the first burst of business, it more than sufficed for all Dick’s moderate wants; so that he occupied an apartment at the Wallace Inn, cracked his jest with impunity even upon mine host himself, and lived in respect and observance with the chambermaid, hostler, and waiter.

Those halcyon days were too serene to last long. When his honour the Laird of Gandercleugh, with his wife and three daughters, the minister, the gauger, mine esteemed patron Mr. Jedediah Cleishbotham, and some round dozen of the feuars and farmers, had been consigned to immortality by Tinto’s brush, custom began to slacken, and it was impossible to wring more than crowns and half-crowns from the hard hands of the peasants whose ambition led them to Dick’s painting-room.

Still, though the horizon was overclouded, no storm for some time ensued. Mine host had Christian faith with a lodger who had been a good paymaster as long as he had the means. And from a portrait of our landlord himself, grouped with his wife and daughters, in the style of Rubens, which suddenly appeared in the best parlour, it was evident that Dick had found some mode of bartering art for the necessaries of life.

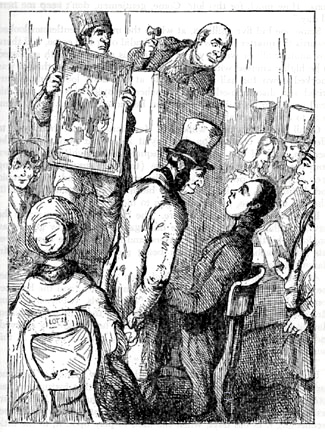

Dick, who, in serious earnest, was supposed to have considerable natural talents for his profession, and whose vain and sanguine disposition never permitted him to doubt for a moment of ultimate success, threw himself headlong into the crowd which jostled and struggled for notice and preferment. He elbowed others, and was elbowed himself; and finally, by dint of intrepidity, fought his way into some notice, painted for the prize at the Institution, had pictures at the exhibition at Somerset House, and damned the hanging committee. But poor Dick was doomed to lose the field he fought so gallantly. In the fine arts, there is scarce an alternative betwixt distinguished success and absolute failure; and as Dick’s zeal and industry were unable to ensure the first, he fell into the distresses which, in his condition, were the natural consequences of the latter alternative. He was for a time patronised by one or two of those judicious persons who make a virtue of being singular, and of pitching their own opinions against those of the world in matters of taste and criticism. But they soon tired of poor Tinto, and laid him down as a load, upon the principle on which a spoilt child throws away its plaything. Misery, I fear, took him up, and accompanied him to a premature grave, to which he was carried from an obscure lodging in Swallow Street, where he had been dunned by his landlady within doors, and watched by bailiffs without, until death came to his relief. A corner of the Morning Post noticed his death, generously adding, that his manner displayed considerable genius, though his style was rather sketchy; and referred to an advertisement, which announced that Mr. Varnish, a well-known printseller, had still on hand a very few drawings and painings by Richard Tinto, Esquire, which those of the nobility and gentry who might wish to complete their collections of modern art were invited to visit without delay. So ended Dick Tinto! a lamentable proof of the great truth, that in the fine arts mediocrity is not permitted, and that he who cannot ascend to the very top of the ladder will do well not to put his foot upon it at all.

Sir Walter Scott. 1771 – 1832

Title: The Bride of Lammermoor, 1819.

You must be logged in to post a comment.